Diez tapped the ring on his right index finger against the fob. The flatscreen panel in what looked like a solid metal door appeared and scanned his face. At the prompt he leaned forward for the retinal scan.

By rote, he spread his arms and legs. Like Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, he thought to himself. He couldn’t help but wonder where the famous sketch by the artist ended up, or if it survived. It was traditionally housed in Venice. He knew that. Sometimes borrowed by the Louvre. So much great art lost.

As the pulse of the infrared camera dissipated, Diez returned his arms to his side, pulled from his thoughts when the green light framed the screen, his signal for all clear.

Nothing to hide.

A thought even the precise and invasive lenses and sensors couldn’t detect. If they could, would they believe him? Would he believe himself?

Today’s confession was in LA on the backlot of a once great studio, where the big show was filmed. He preferred the lot in Calgary, which was closer to home. But he was itinerant and the Loop made for a fast trip.

He stepped through the door into the lobby. The entryway, geometric panes of glass restored since the looting and the fires that preceded them had almost put the city out for good, reflected light throughout the room. It reminded him of the great windows of Notre Dame for some reason, though there was no stained glass. The height, perhaps.

He stopped to look up at the light. Couldn’t help himself. He let it seep into the skin. Penetrate the lines of his face. He stood there in a beam of sunshine palms out turned. Didn’t care what the production staff buzzing to and from corridors that led to the sound stages might think.

He took a deep breath, aware he couldn’t prepare for what the next few hours would bring. He would quiet his mind, even here. Especially here. He inhaled deeply, inhaled the earthy, welcome smell of the greenery in the lobby’s atrium. Blossoms of an orange tree. The sharpness of fertilizer. Dirt.

He had stood like this, in Notre Dame. Eyes closed. Transported. The light through the glass of those windows had done it then. Years ago. When it reopened, after the fire that burned through it. Before it was lost, forever, along with everything else in that great city.

“Father Diez, welcome.”

He opened his eyes. He didn’t recognize the voice. The woman with the headset stood at a respectful distance, the impatience of a production manager: the ponytail quickly pulled into place, the half smile that turned down slightly at the corners of her mouth because the muscles were so used to frowning, her one flash of eye contact, then the return of her gaze to her watch.

“Ready for me?” he asked.

“Right this way.” She was already walking. “The people have spoken.”

***

He followed her through the lobby, past the reception area where the production crew came on break to grab a bite to eat, sit in the sun, gossip.

He could have walked it himself, he was familiar with the corridors, but it was a carefully guarded set, for good reason. As they approached the red room, they walked the gauntlet of souls—his term—the long corridor with photos of contestants on each side. Those who won and walked away. Those who did not. They looked at each other from their frames, the flat images in black and white more film noir portraits than mugshots.

Some of the most famous people in Corridor West, they were made up to look like movie stars. “No need to lead the witness,” the show runner once said when he asked why they looked so glamorous. “It adds to the drama, and makes for great promo.”

The necessary, ongoing evil of Corridor West. The terrible thread that wove through the new social fabric that kept it from ripping here. Stay in line, do your part, contribute and live a quiet life, and you’ll do fine. Step out of line, you’ll be gamed.

Justice turned over to the people, broadcast and streamed. Absolute.

Life is nasty, brutish and entertaining.

They walked in the direction of the sound stages, a maze of hallways that connected an intricate series of rooms where cameras rolled. He greeted the production assistants and crew with nods. Faces that were familiar. The people that made the game a reality.

The production manager knocked twice on a door and it hissed open. She nodded and was gone. He entered a room at the end of the hall after logging his arrival with a tap of his ring. There were two security personnel in this room. He smiled at them and they nodded back, not a word exchanged.

He knew the routine.

Priests and other so-called holy women and men throughout the centuries had different rituals associated with their orders and practices, some more elaborate than others.

He thought of the order of Levites. All the men of the priestly tribe were washed, dressed, anointed with oil in front of the tabernacle when they were first ordained. Before they entered the service they placed their hands on a bull before it was sacrificed. Followed by two rams. Offerings. Absolution.

Together they would make a meal of one of the rams, the ram of ordination. But an outsider shall not eat of it. Only the high priest could enter the holy place.

The inner sanctum of the terrible gameshow had, for better and for worse, become one of the main shared experiences for the people of Corridor West. A shared social experiment. A secular sacrament, so to speak. And here he was in the middle of it.

He’d quickly developed his own little ritual. He was aware with each movement of the emptiness of the rituals people perform in front of others who don’t understand them or adhere to the system of worship they represent. Outward acts of performative religion.

First he removed the ring from his right index finger. Without it, he and most anyone else in Corridor West were invisible. Not entirely. But nearly. It was the quickest identifier and tracker. Key and meal ticket. Opener of doors and acquirer of food and other life-sustaining resources. And the first line of defense against sickness. It monitored key biometrics through a series of sensors against the skin.

Next was the ring on his left index finger. The earthly possession that meant most to Diez. He turned it once, massaged the kub of bone above and below the metal, slowly worked it over his knuckle. He placed it gently in the plastic container beside the other ring.

He looked at the male guard after he put it down. The man nodded back.

Diez pulled his phone out next, from the inside pocket of his coat and placed it in a bin. Then he removed his coat, unlaced his boots and removed his socks. He had flashbacks to the days when air travel in airplanes was the main mode of transit for long distances. The long lines of airport security ended in the inconvenient, even ridiculous removal of shoes, boots, liquids, pens. How antiquated that seemed now.

But it stopped there, at the removal of boots and belts. Here, in the quiet rooms of the studio complex, he slipped off his shirt and undid his pants. He dropped them in a larger bin beside the ring.

He looked at the security guards again. Both the woman and the man had bored looks on their faces. Two people whose names he didn’t know who knew his body more intimately than any other human on the planet. Despite their bored expressions he noticed they both looked, reflexively, at his abdomen.

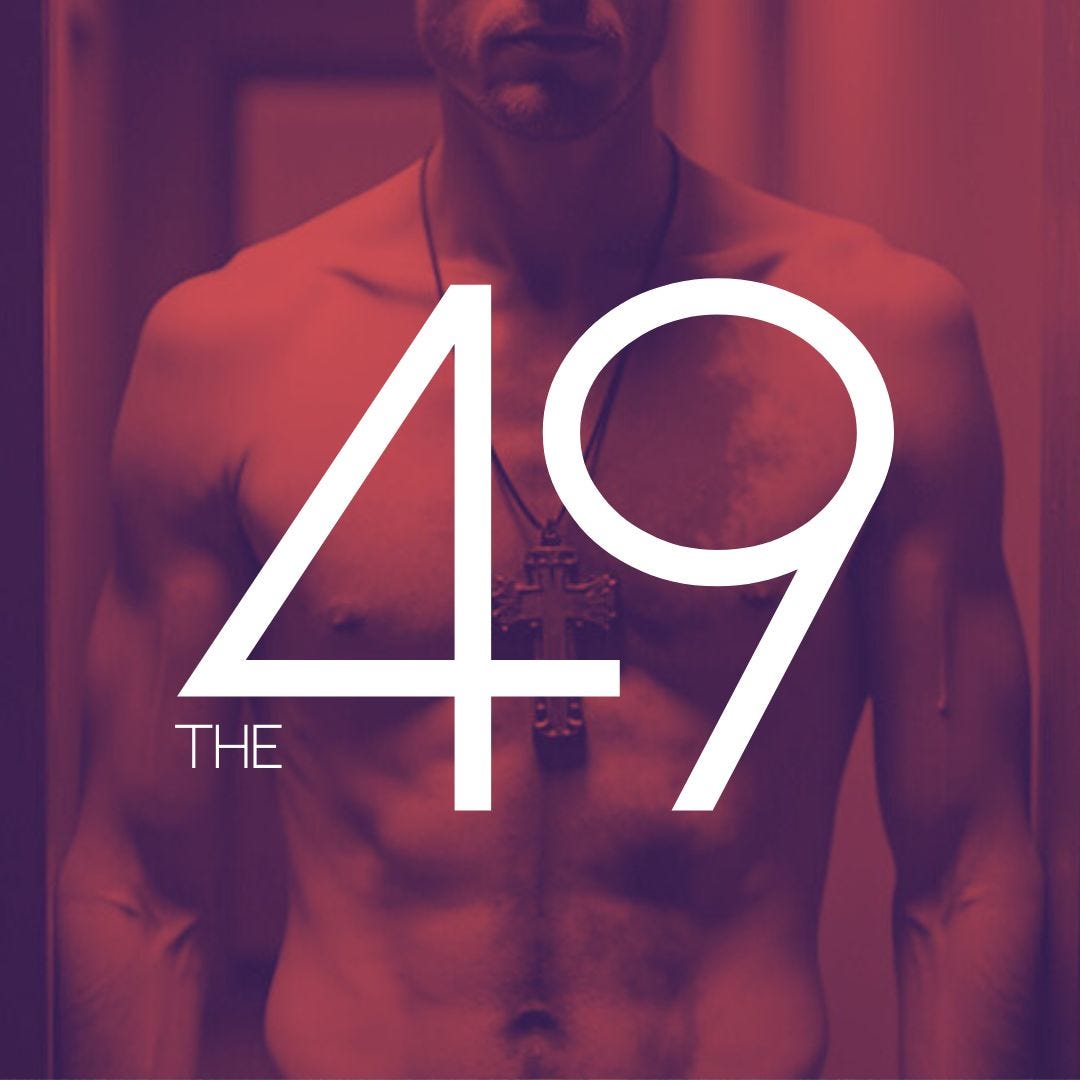

He stood in his underwear with only a wooden cross around his neck. A gold square was laid into the wood at the centre, connecting the vertical and horizontal beams. In the centre of the gold was a red ruby. The cross was attached to a green cord that hung to his abdomen, between his sternum and belly button. It rested on a scar that time had not healed. It was raw, like the wet skin of a tongue. He never got used to the sight of it himself, if he happened to see himself in a mirror.

His stomach was flat, chiseled even. Intaglio. Like a hand had carved sharp lines into his torso. The food shortages had weaned Corridor West of excesses that bloated so-called developed populations for centuries. But the muscle was also part of his assignment. It helped ratings, he was told. So to get his full rations he had to keep to a fitness routine.

The scar created a strange contrast to the cut of his stomach, like a sculptor had mixed mediums, added a wet entrail of clay in bas relief, that protruded at his oblique muscle and whipped up to his rib cage. A startling line, further contrasted by the wooden crucifix and green cord holding it in place.

The security personnel knew not to ask for him to remove it. They knew the routine as well.

But he did remove it, after dramatically crossing himself and whispering a prayer in Latin. He held the crucifix to his forehead, kissed it, then carefully lifted it from his neck. He placed it beside the rings, as though he were putting down a newborn in its crib, careful not to wake it.

To Diez, it was the most ridiculous part of the whole performance, but to the guards it always seemed to convey the most significant part of the charade that was the show. The performance of Corridor West.

He inwardly chastised himself. Forgive me. The cross still meant something. Even here. To him. He’d have to think about that, later, when he could contemplate.

He opened his hands to both guards and smiled. There was nothing left. They nodded at him and signaled for him to walk through the scanner. When he turned to walk through the sensors, they saw the burn marks and scars on his back. Enough to make someone wince at first look. But these guards didn’t flinch.

Of course the scanners could sense any contraband he or anyone else might try to smuggle into the chamber beyond the doors. But this was all part of the show. The film crew, hidden in the shadows on the other side of the doorway, would capture the moment he walked through the door. The priest, stripped down and vulnerable, just like the contestant, there to deliver the last rites to whoever it was behind the door.

It was the big reveal of every final episode. Who got the vote. Who would live and who would die. And the strange story of his body, what it told to the camera—the vitality, the tragedy lived out by a priest of all people—helped set up the high stakes of the climax of every show, when the camera punched in and captured the look on the person behind the door who, like the rest of the viewing audience, was learning their fate live, in that very moment.